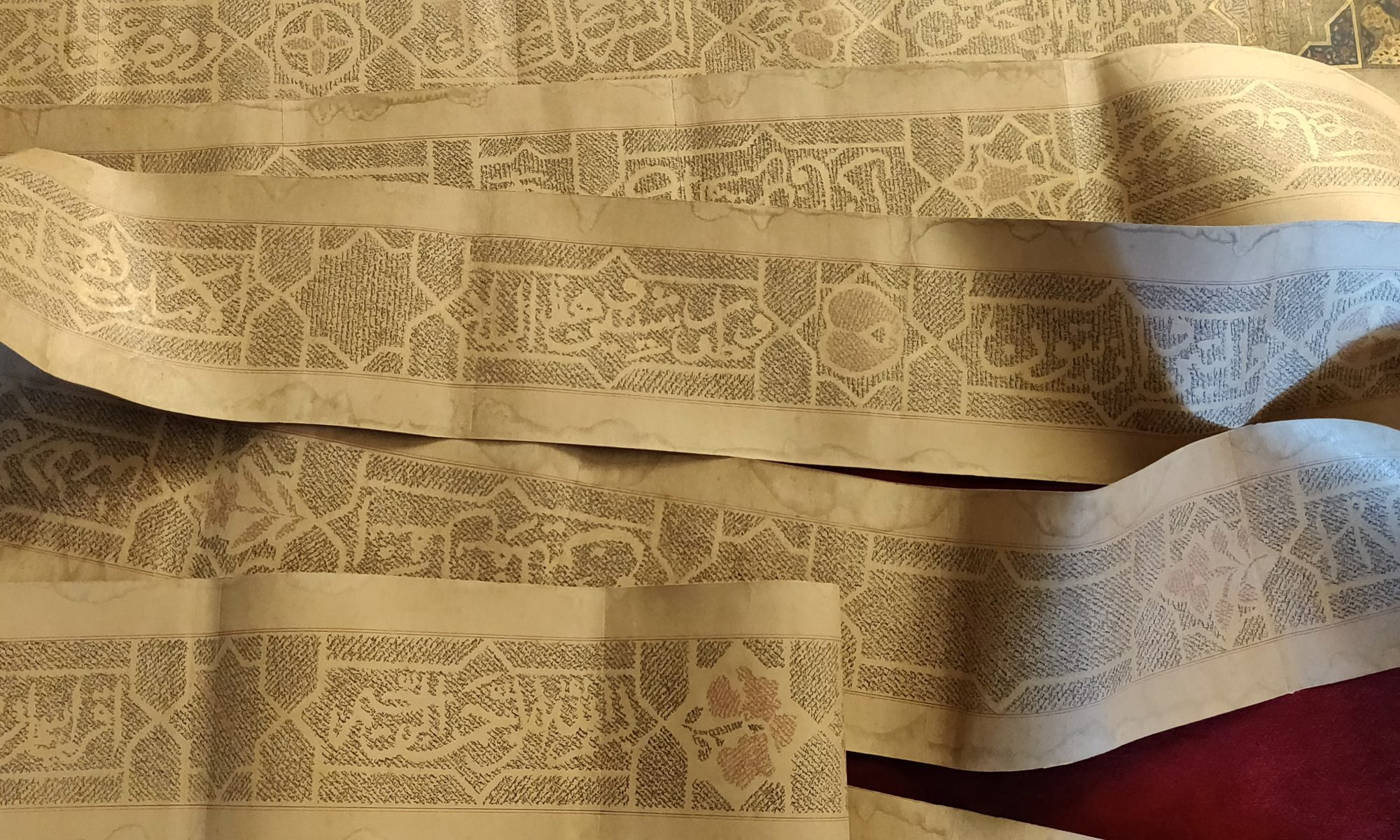

Much has been reported and published on the two leaves of an early Qur’an Manuscript that has come to be known as the “Birmingham Qur’an”. The “Birmingham Qur’an” is an expression regarding two leaves of an early Qur’anic manuscript written in the Hijazi script that was dormant in the Mingana Collection at the University of Birmingham ( Accession # 1572a). The folios in the Birmingham collection are parts of Surahs: Kahf, Maryam, and TaHa. After Dr. Abla Fedeli, a researcher at the University of Birmingham, published her findings, many celebrated and spread baseless news through media reports, social media, or hateful Islamophobic outlets. This article is an attempt to set the record straight and build on the findings of the University of Birmingham and Islamic Manuscript study.

Introduction: How did these Folios get to Birmingham?

In the early 20th century, an Assyrian Chaldean priest named Alphonse Mingana was invited to England by J. Rendel Harris, the director of Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre in Birmingham. After leaving Iraq in 1913, Mingana became a curator of Arabic manuscripts and an Orientalist who was tasked by Edward Cadbury, founding member of Cadbury Chocolates, to travel to the Muslim world seeking manuscripts for his collection. Edward Cadbury was a chairman at the college’s council and had known Mingana through the college library. Between 1924 to 1929, Mingana had traveled to the Muslim world seeking the rarest and oldest manuscripts. Edward Cadbury, a Quaker Philanthropist, himself was not well-versed on Islamic Manuscripts, which is why he employed the expertise of Alphonse Mingana (Fedeli, 2011). The story of this valuable piece of Islamic history and knowledge is a common narrative since the 19th century. Many Islamic manuscripts found their way into Western, specifically European, collections and libraries in this period. There are currently over 3000 Arabic manuscripts in the Mingana Collection at the Cadbury Research Library in the University of Birmingham.

Other Folios from the same Qur’an and their Origin

A group of folios (16ff.) of the same Qur’an can be found in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Arabe 328(c)). Francois Deroche documented the provenance of these folios (Deroche, 2000). When the French Orientalist, Jean-Luc Asselin de Cherville, served as Vice Consul in Cairo from 1806 to 1816, he obtained numerous manuscripts that he purchased from the Grand Mosque, Jaami’ ‘Amr bin Al-‘Aas; which was the first Masjid built in the entire continent by the great Sahaabi, ‘Amr bin Al-‘Aas (d.44H/664CE) . Cherville, took these manuscripts to Paris and they were purchased by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in 1833 where they remained until today. Dr. Qaasim as-Samara’ee, a leading Arabic Paleographer, argued that many of these manuscripts taken from Egypt in the 19th century were, in fact, stolen or taken by force and deception (As-Samara’ee, 2015). This narrative of Islamic manuscripts that were stolen or taken by deception or force in the 19th and 20th centuries is well-established (Ghobrial, 2016). Sadly, this behavior still continues today.

The Findings of Dr. Alba Fedeli’s Study

The folios of 1572a remained in the Mingana collection since 1930 with an inaccurate dating that was determined decades prior. Dr. Alba Fedeli studied these manuscripts and noticed that these two folios were incorrectly compiled along with a different Qur’an manuscript dating to the late 7th Century CE. She requested a Radiocarbon analysis (C14) that yielded a date range on the parchment of 568 CE to 645 CE with a 95.4% confidence level (Fedeli, 2015).

Misinterpretations of the Media and Deceptions of Islamophobes

After the study was published, the media picked up the results and numerous conclusions were thrown around. Notions that this manuscript proves that the Qur’an was plagiarized since it was written before the Prophet Muhammad صلى الله عليه وسلم was born or received Prophethood (البعثة) circulated among Islamophobic circles. The Prophet Muhammad صلى الله عليه وسلم was born in roughly 570 CE and after 40 years, he attained Prophethood (610 CE) and then he died in 632 CE. Of the period given by the Radiocarbon Analysis, the majority would indicate doubt according to the Islamophobes. This accusation is a clear attempt to attack Islam and does not represent a sincere attempt to understand the findings of Dr. Fedeli’s analysis.

The Radiocarbon Analysis tells us the estimated period when the animal used to make the parchment died. The Radiocarbon, or Carbon-14, analysis is conducted on organic material, in this case the parchment made from animal skin, and measures the amount of Carbon-14 in the sample against an international reference standard. Based on this number generated based on the Carbon isotopes present in the sample, an age estimate is given for the material (Bowman, 1990). It is important to understand this: Radiocarbon Dating tells us an estimate of when the animal was alive, it does not tell us when the material was used.

Therefore, regarding the ‘Birmingham Manuscripts’, we can say: the unidentified animal used to make the parchment was alive during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad صلى الله عليه وسلم or just over a decade after his death. We absolutely do not know with any certainty when this manuscript was written. We can only assume that this is a very early copy of the Qur’an based on the closeness to the time the parchment was made.

Misinterpretations of the Muslim Community

After the media reports, many in the Muslim community began to claim that this Qur’an was either written in the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad صلى الله عليه وسلم or a pre-‘Uthmaan copy. Both these notions are unprovable and are simply problematic assumptions that only rely on the carbon dating results.

It is a faulty methodology to solely rely on carbon dating and ignore the other evidence taken from historical references and paleography. C-14 Dating is rarely used on Islamic manuscripts as more reliable methods include paleographic analysis, codicology, material study, and historical research. Dr. As-Samarra’ee (2015) argued that one must also factor in the possibility of contamination of the sample during its creation or during its testing that may lead to inaccuracies in the results. Atmospheric variations must also be considered when analyzing the results of the estimated range. Other scholars of the field, such as Dr. Ibraahim Azwagh al Faasi, mentioned that they’ve found discrepancies in testing. Similarly, leading Orientalist Islamic Paleographer, Francois Deroche expressed concerns about relying on C14.

Since the practice of writing the date on colophons did not occur on Qur’anic manuscripts until roughly the 4th century, every date range given to a Qur’anic manuscript is an estimate based on research. It is impossible to ascertain without a significant element of doubt. This is why dating in this period is often done with a century rather than a specific date or ascription. The ‘Uthmani compilation would have occurred after or around 650 CE, which falls five years past the date range given by the C14 Dating. There is absolutely no evidence that indicates that this was the Mus-haf written by ‘Uthmaan رضي الله عنه or that it is a pre-Uthmanic Mus-haf.

Due to the expense, parchment was often used within a short period of time after its production, likely not exceeding a decade or two. A well-known Qur’anic Paleographer, Dr. Qassim As-Samarra’i (2015) asserted that upon his analysis he determined that this manuscript is a Palimpsest; meaning that the parchment was reused. This theory increases doubt in ascribing this manuscript to the period soon after the death of the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم. However, the University of Birmingham conducted a Multi-Spectral Imaging analysis (MSI) that does not show any evidence that this manuscript is a Palimpsest.

Given this information, it’s not probable to claim that the Birmingham Qur’an is the Qur’an of ‘Uthmaan رضي الله عنه or that it preceded him and is a pre-Uthmanic codex.

Conclusions on the Birmingham Qur’an

Using all the available information and research, the conclusion that makes the most sense is that the Birmingham Qur’an Folios dates to the mid to late 7th Century after the death of the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم and likely during the time of the Sahaabah- after the codification of the Uthmanic script. It is impossible to state that this is the Qur’an of ‘Uthmaan رضي الله عنه. Some researchers noted that based on its provenance, we could assume that it was after the conquest of Fustat and the establishment of the Muslims in Egypt. Researchers from the Birmingham University also concluded that it is more likely based on these findings that this manuscript was written roughly 2 decades after the death of the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم.

The Birmingham Qur’an yields the earliest result of several other Qur’anic manuscripts that have been dated to the late 7th century. Of them are the San’aa Palimpsests that were dated with a 99% confidence interval to 671 CE and 75% confidence interval to 646 CE, the Tübingen manuscript dated between 649-675 CE with a 95% confidence interval, the Tashkent manuscript (Samarqand Qur’an) dated to 765-855 CE with a 95.4% confidence interval (University of Birmingham, 2018).

It’s clear for us to say that this manuscript is possibly an earlier codex written in the late 7th century well after the death of the Prophet Muhammad صلى الله عليه وسلم. It should be noted early Qur’anic manuscripts do provide valuable insight in the field of Orthography (Rasm al Mus-haf).

References:

As-Samara’ee, Q. (2015). Qur’an Palaeography and the Fragments of the University of Birmingham. Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation. London, UK.

Bowman, S. (1990). Radiocarbon dating (Vol. 1). Univ of California Press.

Déroche, F. (2000). Manuel de codicologie des manuscrits en écriture arabe. Bibliothèque Nationale de France-BNF.

Fedeli, A. (2011). The provenance of the manuscript Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572: dispersed folios from a few Qur’anic quires. Manuscripta Orientalia. International Journal for Oriental Manuscript Research, 17(1), 45-56.

Fedeli, A. (2015). Early Qur’ānic manuscripts, their text, and the Alphonse Mingana papers held in the Department of Special Collections of the University of Birmingham (Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham).

Ghobrial, J. P. (2016). The Archive of Orientalism and its Keepers: Re-Imagining the Histories of Arabic Manuscripts in Early Modern Europe. Past & Present, 230(suppl_11), 90-111.

The University of Birmingham. The Birmingham Qur’an Course. May 2018.